Sir Ferenold Stormshend is a writer, politician, nobleman, and noted intellectual. A teacher of both Kaldorei and Gilnean druidism within the Howling Oak, he came to public prominence in the same area, emerging as a rousing orator whom possessed what was described by one quaint gentle-man as "Near-apoplectic" rage. Apparently touching on at least some feeling common in Gilneans, Sir Stormshend rose from the child of a little-known borgiousie trader and illegitimate headlands noble to one of the most influential figures within Gilnean society: both amidst the literary intelligentsia as well as the great mass of Gilnean refugees.

A self-described 'reactionary' in the political sphere, Stormshend's opinions are wide-ranging, controversial, and often repulsive to liberals and conservatives alike. Despite the ambiguity often inherent in the man's beliefs, there are several elements of his idealogy that are clear: he is a firm defender of aristocracy, tradition, and landed wealth - as well as a resolute enemy of industrialism, secularism, and all forms of utilitarianism.

Sir Ferenold Stormshend, Lord Vanston, and Lord Torean Austerlitz established the Order of the Elder Orchid, with the goal of repopulating the Southern lands of Gilneas. After the latter two defected from the Orchid, Stormshend became its official leader, and under his leadership the Township of Darel'horth has been established in South-central Gilneas.

Parents.[]

Despite certain tales to the contrary, Sir Stormshend was hardly born from humble beginnings. His father, Thomas Stormshend, came from a long line of merchants and tradesmen that were formerly yeomen until the class faded into obscurity. Born in Duskhaven, he moved to the city at the age of twenty-two in search of both a wife and the ability to expand his economically strained textile company. It was there he met Emilia Keann, an 'illegitimate' noble of the headlands whom had recently traveled to the city, seeking a vocation with the church.

She had essentially been stripped of her nobility when she was formerly exiled from the Headlands territory held by house Llarenwyn, one of the few remaining houses that still held ties to the pagan peoples of Gilneas. Banished for committing adultery, she fled to the city where her aristocratic demeanor and wealth allowed her to easily become a priestess within the Gilnean clergy.

Despite both immense cultural and philosophical differences that would later open a rift in their marriage, Thomas Stormshend married Emilia after a brief time courting her. Her first and only child, Ferenold, was born precisely a year after they married.

Early Life.[]

Mister Thomas Stormshend was a wealthy man - but not one wealthy enough to escape to the quickly-growing suburbs at the edges of Gilnean city. Hence Sir Stormshend lived for much of his early years in one of the relatively dignified houses in the Merchants District, possessing a parlor and all the traditional elements of a small Gilnean manse at the time. The household was a relatively amiable environment, if one that was also dull, with relatively little artwork or cultural fixtures.

Emilia Stormshend insiste

The house where Ferenold was born. (Gothichouse.jpg, source unknown)

d upon caring for the child by herself, and herself solely, which struck Mister Stormshend as somewhat nonsensical at the time. Nonetheless, the man relented, and allowed for the mother to be the primary caretaker of Ferenold. From a young age, Sir Stormshend was filled with the esoteric knowledge of the headlands, and the oral tales that their people were famed for. His mother could be seen even in the later hours singing hymns to the child - and she often took him to the Cathedral of Gilneas, where she worked.

Several journal entries of Emilia Stormshend shed some light upon Ferenold's early years:

May 22nd, year 1028 in the Gilnean Calendar,

I find that young Ferenold possesses a most apt mind for the discernment of texts, and a great joy for various forms of story-telling in all aspects. However, I worry often at the boy's fate at the hand of Thomas...undoubtedly, it is he who shall make the final decisions upon his fate, but the boy does not have a mind befitting of a tradesman, and it would be cruel to thrust a literary mind into economics. He would do most good for the church, an institution which may guide his mind in the proper directions,

Emilia Stormshend.

August 7th, year 1029 in the Gilnean Calendar,

I fear that Thomas was correct about the boy's position in the church. His spirit is far too wild and tempestuous, and regrettably the most holy Light seems only to add to these flames. He was most generous to allow the boy the chance of entering the clergy, but now I must concede that he must be sent off to the boarding school,

Emilia Stormshend.

The first rift of note within the marriage of Thomas and Emilia Stormshend occured in this year, from 1028-1029, when Ferenold grew from six to seven years of age. Emilia vehemently wished for the boy to enter into further studies at the Cathedral to eventually becaome a pastor, believing the boy had an imagination that ought not be quelled, but rather re-directed into the clerical studies of the search. Thomas sought to leave his textile business in study hands, and for him -lineage- was of the utmost importance.

In many respects, this tension was merely the manifestation of larger problems that were surfacing within the marriage. Emilia had hidden much of her aristocratic past, knowing full-well that few men would take on a woman that committed adultery, ruined a marriage, and then fled from it. Hence her past was something of a mystery to Thomas, and when the man sought to learn more of it conflicts inevitably arose. Thomas had become more and more disillusioned with Ferenold himself, whom displayed none of the attributes which he so dearly cherished.

To further compound his anger was Emilia's infertility. After having birthed Ferenold, she grew pregnant only once after, and suffered a miscarriage. Emilia, whom was once a reserved woman that found solace in the church but still had small moments of passing cheer, now grew altogether solemn in her demeanor. Eventually the problem fixed itself, when this solemnity gave way to utter servitude, and she thereafter gave away her past to the man: all of its shame and sorrow.

This only threw Thomas into a more indignant rage, whom believed himself to be decieved. And yet, this upwelling of emotion transformed the cold, mechanical man into a lover of tragedy - as if through the witnessing of complete solitude and lost love, he may be relieved in some manner of a catharsis. He was seen frequenting theatres often, without wife or child.

Life at Boarding School.[]

At the age of ten, Ferenold was sent to the Wiltfortshire Academy for young men. It was a school known for its strict disciplinary measures, and near-universal focus upon the more mundane facets of life. It was located upon the other side of the city, around two hour's walk, in the 'Royal District'. Yet it was certainly not a school meant for nobility. Composed solely of men, the school primarily put out those skilled in ledger-keeping, trading, and economics. There was also a heavy focus upon the history of Gilneas, with a heavily nationalistic bent. At the age of ten, a professor wrote the following of Ferenold:

"The boy is generally quiet, possesing little rudeness in his own, and being generally well-skilled in manners. He possesses a certain fragility which ought rightfully be corrected, as his mien and behavior seems more characteristic of the feminine sex. Such being said, it is worth noting that the boy has been endowed with a certain peculiar intelligence, whereby he can discern the meaning of literary works through mere intuition. His interactions with the other children appear generally rigid and forced, however, more befitting of a scientific, detached mind than a literary one."

Another professor wrote:

"Ferenold seems to be altogether a most delicate, and sensitive soul, as some manner of over-dramatization of the tortured romantic. To me, it appears that he is driven in his actions by some sense of perpetual fear, and it is perhaps this unique fear that grants him the ability to comprehend the texts with such great clarity. I do look forward to seeing the work that he produces, though I fear he will not come to truly appreciate the laws of style."

Ferenold did indeed bask in literature at an early age, being most fond of the old courtly romances as well as Gilnean romantic texts. He very much enjoyed the new form of the novel, and he believed that his future profession laid in creating one himself one day. Despite his newfound interest in books - which the school had plenty of, he still had a feeling of alienation from the school, and GIlneas City in general. There are a variety of factors which caused this isolation...

Wiltfordshire academy for young men. (boarding.jpg, old city of Baku photo)

Perhaps the most obvious was the boy's homosexuality, which came to occupy him at the age of thirteen. Ever the thinker, he believed it naturally to be some manner of a perversion, and he strove with great vigor to free himself from it after overcoming the initial confusion. He could not, of course, and thus he experiences, hed a sort of inward-looking demeanor which isolated him from the school. Occupied with his own problem, he was wholly unable to connect to the world.

Secondly was the focus on debate, didactic, and rhetoric in the school. When he was not learning of the economics and the sciences - fields he thoroughly despised already, he learned of literature in order to argue about its merits. Argument and debate not only were foreign to the boy, but they ended up being deeply repulsive to him as well. His voice high-pitched and stuttering at a young age, he had little skill in it and even less enjoyment of it.

Thirdly, and lastly, was the growing distaste of the boy for city life. Each summer, he would depart from school and go to the headlands with Emilia, where they had recently purchased a small summer house. Taking hold of the boy's mind with the fervor of some fanatical teacher, Emilia denounced city life and city virtues. This attack truly intended to disparage the father, but the boy took it literally - greatly admiring his mother, and greatly impressionable as well, he came to share her beliefs.

As the years passed, Ferenold grew more and more sundered from the intellectual life. The love of reading he once had mostly whittled away, in favor of a child-like love of the primitive and instinctual. His grades accordingly suffered, but at this point the father was living too much a life of his own to have over-much care of the boy: indeed, Ferenold hardly saw him in the first place, so engrossed he was in tragedy and a growing mysticism of his own.

Upon one summer visit of the headlands, when he was fifteen, Emilia told him of the Keepers of the Elder Ways. At once, a force gripped the boy's interest that was tantamount to his earlier passion of reading. Thoroughly lifted out of the doldrums he had dug for himself, he now occupied much of his time at the boarding school in searching for texts which merely mentioned the Elder Ways, in an attempt to learn them himself. At the age of sixteen, a series of momentous changes came about that caused the boy to leave the boarding school.

Departing the Boarding School.[]

On the 18th of July, of the year 1038 in the Gilnean Calendar, Lord Darius Crowley was imprisoned for treason against the throne of Gilneas, leading to what would eventually be the Northgate Rebellion. Both Thomas and Emilia Stormshend supported the rebellion: Thomas for economic reasons, and Emilia for idealogical ones. Their kind, rebel sympathizers, was exceedingly rare within the city of Gilneas, which was they ernomously pro-loyalist. Much the same time that these tensions first flared in Gilneas, troubles came forward in Ferenold's own life.

Living in some manner of an enchanted dream-world with the Elder Ways, his grades had plummeted and his father had threatened to personally administer discipline. More intensely isolated and alienated than ever, his 'problem' was only furthe

The forest between Gilneas City and the Headlands. (Forest.jpg, dark forest wallpaper)

r complicated by the frequent harrassment he recieved from other students at the time. Fed up with what he would later term "Decadent Urbanity", on the night of October 14th he would sneak out of the school for what was to be one of his usual 'forest-walks' - periods of reflections that he found some comfort in.

In this case however, he never returned to the school. Intrigued by what he now claims was a mystical vision, he strode on foot over to the Headlands. This walk took merely three days for the boy, but it had bore monumental changes for Ferenold. Recalling his past literature and the 'sublime', the boy believed at this time that it was in contact with nature that one was closest to the divine. Presumably hearing whispers from the forest-spirits, he was driven to the headlands in search for a man who might be able to grant him answers.

His depature did not go unnoticed by his parents. Both of them grew most upset after learning of the boy's departure, and the agony that each of them would endure would eventually bring them closer together once again.

Arrival into Awnfenn and work.[]

Ferenold was still at the age of sixteen when he came into the village of Awnfenn. A small town consisting of around 1,500 people, it was relatively prosperous due to the natural irrigation that it received from the river of Earl'forth. Both incredibly intrigued and incredibly fearful of his new encounter with freedom and the rough-spun locals of the headlands, he resolved to stay in Awnfenn until he could find a man to teach him the elder ways. The endeavor seemed most hopeless at first - not a single man or woman in the town knew of any 'Keepers of Yore' that lived nearby.

Finding it necessary to take up some manner of work in order to survive, Ferenold made acquintance with a man known as Sean O'connor, a local politician and butcher. He was hired as a courier, and the jo

A romanticized portrayal of Awnfenn. ( Awnfenn.jpg, deviant art painting of primulatook)

b befit him greatly. It was required that he learn thoroughly of the local terrain that the headlands possessed, and he made it his solemn duty to explore the lands as well as the various towns near Awnfenn. During these three months, the boy's demeanor changed greatly.

Gradually re-creating himself, he abandoned much of his prior city manners, and his words gradually acquired the local headlands accent. He met a variety of colourful characters in the various towns that he ventured to, and set aside time for himself to commune with the forests. In reality, his efforts were completely fruitless, but the boy possessed the imagination of a child even at this older age, and hence he truly believed that he was first touched by the Elder Ways by no hand but that of the forest.

He grew to have a certain fondness for an older woman by the name of Colleen the crone, whom ran a herb-shop in a village just to the west of Awnfenn, also along the river of Earl'forth. For the latter month of this three month period Ferenold lived with her, renting out a single room of her household. He only left when she finally recalled an old man that she had once met, by the name of Farlund Isenstrider. Reportedly some manner of a Bard, Ferenold at once left to search for the man.

Farlund Isenstrider.[]

What manner of a man is this Farlund Isenstrider? His tale is too long to tell here, but may be recounted with merely the basic archetypes intact. He is a headlands man through and through, born of a noble family, one of the few that still practiced the Elder Ways. When the noble family was forcibly disenfranchised and pushed off their land, he left Gilneas to wander the world, visiting Lordaeron, Arathor, and Alterac before returning to Gilneas to find the Headlands thoroguhly changed.

As a youth he grew to be angered at the change and the steady replacement of the Elder Ways by the Light that took place, but over time age cooled his passions. He was one of the first to consider himself n

(Farlund.jpg, Imaginative illustration of 'An Arch Druid in His Judicial Habit', from "The Costume of the Original Inhabitants of the British Islands" by S.R. Meyrick and C.H. Smith (1815))

ot as a mere practicioner of Drurla, Gilnean druidism, but rather one whom actively held unto a tradition that was quickly dying. To preserve it he took up the art of bard-hood, traveling about the headlands, the northgate woods, and even portions of the southern lands in order to both earn himself coin and spread the songs of his forefathers.

As many of his kind did, he grew disillusioned with the world and became a hermit. In appearance he was very much the epitome of the hermit: in sagging brown robes, with a wizened, grey-whiskered face, and bearing both an illuminating lamp as well as a small stick fashioned as a stave. He interacted only rarely with the locals, and kept a small farm for himself blessed by his own hand, through which he fed himself.

For some time he had sought an apprentice - a man whom may carry forth all the information that he had accumulated. In his younger years he had organized a vast compendium of information concerning the Elder Ways, seeking to bring together 'all the wisdom of the ancients'. In personality he possessed all the aspects of an old sage: bitter and cynical at times, split from the world yet intensely connected to it, and still lit faintly by an ember of youth.

Meeting with Farlund. []

Late in his sixteenth year, Ferenold met with the wrinkle-filled old man. He lived in a large, plain wooden cottage in the middle of the woods north of Awnfenn, in a rather discrete and thoroughly tucked away location. It was built directly by hand - Farlund's hand, of course. Farlund's words were spoken with some manner of genuine poetry which Ferenold has sought in vain to match in his own life. Composed and withdrawn, Farlund listened with quiet as Ferenold spoke, and then with miraculous ease accepted the boy as his apprentice.

Naturally overjoyed, Ferenold considered it a moment which would shape the remaining days of his life. The journal that Ferenold still kept elucidates this ecstatic feeling far better than this entry can hope to:

February 1st, year 1039,

I have come upon him at last. After all these months of tiredly searching and groping in the blind darkness, he has come forth before me! I almost feel as if I am compelled to some manner of anger at that old crone for not telling me of him sooner, and yet in such a moment as this I cannot justly be moved to anger, and do not possess the capacity to experience rage. Such a calm has come over me, such a brimming, beating serenity - the forest longing , that yearning we possess to enter the woods comes before me now in person...

What worries I have had over the state of my parents have all but dissippated by now. While I am not one to praise mere repression, in such a state the woes of life naturally become repressed and hidden underneath the grand upwelling which now has rushed over me. I still possess some manner of naivety which grants this whole experience a more nuanced character. For looking upon him, the primary marvel is not the billowing robes or the stave, or the antique glint in his gaze, but the very -fact- of his existence! Were not men as him supposed to be extinct and forg

Farlund's cottage (Cottage.jpg, fine art called 'Fairytale's Ending'.)

otten by now? Lost to the tides of that cruel mistress, history? And yet he still stands, a breathing anachronism and a mystic vessel...

Oh! But I ought not speak of him in such a manner, as if he is merely an object in which I may entomb myself. For he is a man, not a demi-god, possessing all the malleability that a man is wont to have. I feel at once as if the world is not some thing of terror to be confronted, but rather its own being, which I may imitate and bring into myself, which may yet reverse the tragedy which has thus far been my fate,

Ferenold Stormshend.

Farlund looked upon the boy as a child to be taken into and cared for, despite the fact that he was arguably of more ill health than Ferenold. That however, did not stop him from teaching the boy of the Elder Ways and the vast mythology that went along with it. Over time their relation would rise from merely that of a son and a teacher, though - Farlund would become a father of sorts to Ferenold, and Ferenold would cherish him as the first true male guiding figure in his life.

Life with Farlund - the Mundane.[]

Apart from all that Ferenold would learn from Farlund, and apart from all of the influence that the elder man had on the boy, there are still aspects of this life which are worth noting for their normal qualities. Nearly half of Ferenold's day was spent not learning from Farlund, but performing tasks for him. Being an apprentice entailed working for your food, and Ferenold spent much of his time working the farm in the years that he stayed with Farlund.

Each day upon waking, he would first cook himself breakfast - usually some manner of wheat, and then head out at once to tend to the crops for many hours. The boy despised this work at first. Even though he fully preferred rural life to that of the city 'in spirit', he hardly had fond memories of the farm in -reality-! He had to learn much from Farlund to even use the farm properly, and even then he committed a great variety of mistakes and blunders while doing his work.

A road of the Headlands often traveled by Ferenold. (Road.jpg, art of Larry Lane, photo of England)

Thankfully, the fields were blessed, which allowed for the crops to prosper even if a few farming mistakes were made. They were forgiving. But not forgiving enough, evidently. The first harvest that Ferenold oversaw barely had more food than those which Farlund worked on in solitude before Ferenold's coming. As a result, Ferenold had to travel South to the market of Awnfenn to buy much of the food that he required.

He gradually improved in his farmwork, and gradually grew more fond of farming in general, but never achieved the love of it that he would gain from -hunting-. He learned the art in the second year of living with Farlund, whom only taught him it with a large amount of reluctance. Ferenold possessed far more natural skill in the art, and was often found returning with a deer slung across his shoulder.

Ferenold was often sent to various locales in the Headlands to buy various goods for Farlund, necessary for ritual and rite. During these isolated villages to the various townships he grew greatly fond of the people of the headlands, identifying more and more with them as time progressed. During what free time he had away from both his studies of the Old Ways and completing Farlund's tasks, he took it upon himself to seek out women wandering along the forest-paths, courting them with little success.

Life with Farlund - Early Years.[]

The first two years of Farlund represent the time period in which the majority of Farlund's knowledge of the Elder Ways was imparted unto Ferenold. In the last of Farlund's four years with Ferenold he fell ill, causing his ability to teach to sharply detoriorate. It was in these first two years that Ferenold learned what would serve as the foundation for all of his knowledge on the Elder Ways, and go through the training necessary to become an official 'druid'.

Ferenold in the vestments of an apprentice (Druid.jpg, 'druid sketch' by Rachel Kremer)

Farlund began his teachings with the historical tales of the Headlands people and their native religion, wishing first for the boy to get a sense of the context in which he was teaching. Ferenold eagerly accepted and took in this information, but it was later the discussion of forest-spirits, communion with the forest, and active engagement with the soul-world of Gilneas which he would thrive upon. It was when they ventured out to a pilgrimage - notably to the stones of Linwyn, where the boy was struck with the most wonder.

He accepted the ideology with little prejudice or skepticism. After having heard of the gradual destruction of the Elder Ways through questioning and logical debate, he grew distrustful of all attempts to purify a religious belief through questioning. Hence his modern-day admiration of fundamentalists, such as the Scarlet Crusade, despite other major idealogical differences.

Farlund grew more and more fond of the boy as the months rolled by. At first he was skeptical of many of the city-borgiousie attitudes that Ferenold still held, but as Ferenld acclimated to the headlands, Farlund found himself gradually opening up to the boy. Eventually Farlund's own colourful tales grew to be an essential part of the curriculum of the Elder Ways, and a very real emotional investment was placed by the old man in the boy - both as the man that would carry forward the torch of the elder ways, as well as he whom would preserve his own memory.

Ferenold's attachment to Farlund also served to mask the growing worry he had of his parents - and the feeling of guilt that was beginning to pervade him. His kinship with Farlund prevented him from suffering too often from this guild, as long as he had one to continually confide in and speak to, he reasoned that he did not require his parents for the time being.

Life of Thomas and Emilia during Ferenold's absence.[]

The relationship of Thomas and Emilia Stormshend was far from stagnant in the time period of 1038-1042 (Gilnean Calendar), the time period in which Ferenold Stormshend had gone missing. Grief for their departed son brought them together at first - but they likely would have split apart once again, if it was not for the change in demeanor and disposition of Thomas Stormshend. Once the very archetype of the cold businessman whom had shaken off the love of his wife, his love of tragedy seemed to bring the man into a most emotional state once again.

Though hardly as delicate as his son, he gradually transformed himself into a man of culture due to a series of changes in his own life. The Northgate rebellion prompted the Greymane Government to take a degree of control over local industry in order to fund the war effort. Thomas, knowing that the textile business would be next, shut down his shop rather than have it produce the goods that would aid the King's men. He had a large amount of wealth, as well as ample time and a mind wrecked by tragedy not once, but twice.

Over time the marriage became gradually repaired. Though they would never again have what they once did years ago, there was a sort of nostalgic love with each of them cherished. They moved to a large manse in the Headlands with the money that Thomas had earned, fearful of being discovered as rebel sympathizers - and not knowing that they lived only three hours away from their son. A near-religious love of artwork was soon found within Thomas, whom treasured the paintings of the Gilnean landscape and mythic scenes of heroes.

Thomas, ever the extrovert, invited a large number of people over to the house during this time, to participate in ballads and plays. He secretly sent money to the Northgate Rebellion, funding them with the gold necessary to buy arms and munitions. Emilia absorbed herself in other pursuits, the primary of which was teaching the Light at a local parish. More of a constant duty than a mere pursuit, she was seen as a sort of 'mother' to the nearby village, watching over them with delicate solemnity.

Conflicted by the array of feelings he had toward his child, and yet still thoroughly wishing for him to return, Thomas Stormshend and Emilia tried a variety of methods of finding their son - sending out various fliers and other paraphenilia, wandering the headlands of their own accord, and even looking through the census records of various villages. The failure of their search did not cause greater conflict within the marriage itself, but it did create a certain feeling of futility which rendered them unable of true happiness.

Life with Farlund - Late Years.[]

During the late years of Ferenold's stay with Farlund Isenstrider, the man fell ill to old age. It was not some manner of disease that had taken hold of them, as populous and deadly they were in a contained nation such as Gilneas. It was merely the progressive fraying of both his bones and his mind that had led him into such a state. Ferenold felt deeply indebted to the man, whom had given him an entirely new vision of the world. He cared for Ferenold in his final years - up to his very death.

Ferenold's psychological fragility was displayed with full force during this time. His entire world, which for two years had rested upon Farlund's shoulders, was gradually crumbling as Farlund's life slowly whittled away. The boy - or rather young man now, displayed all the signs of denialism. Frequently Farlund encoruaged Ferenold to recognize that the end of his days had come at last, but Ferenold stood staunchly against coming to terms with it.

The paradox of the situation is that Ferenold did very much care for the old man in his final years. Their entire position now reversed, the majority of Ferenold's days was spent caring for the aging man. Many of their most heart-felt conversations took place in these times, and Ferenold belatedly took up writing once more under the encouragement of Farlund, which he had abandoned after learning of the Elder Ways.

Ferenold's devotion to Farlund was near-fanatical, albiet often hidden behind pleasantries. Farlund however, encouraged the boy to escape the cottage, urging him repeatedly to venture toward the various sacred places which they once explored in younger days. In line with the alienation and isolation he had faced before at boarding school, Ferenold drew himself once more into an 'inward-looking' perspective, coming to believe that Farlund did not understand the position that he held within his life.

Thus it was when the man passed away, Ferenold was greatly devestated. But he also vowed to uphold the man's work, and take on the whole of his idealogy and beliefs without so much as a critical eye for the largest of falsehoods.

Also to note is the role that Ferenold played within the Nrothgate rebellion at the end of Farlund's life. That long-forgotten politician that Ferenold befriended - Sean O'connor, now required his services once more. Ferenold enlisted only reluctantly as a courier of the Northgate rebellion, and under an inexplicable set of circumstances came to take both Farlund as well as Sean with him upon a journey to Llareny, the seat of the rebellion in the Headlands.

Although in support of the rebellion at first, Ferenold eventually grew disdainful of the means of the rebellion, which he felt quite guilty of at the time. A journal further elucidates this:

Year 1042, March 3rd, Northern Headlands,

I was once so enamored with the prospect of rebellion, those marching songs and the gay dances of the peasant-folk, but how quickly and with what disastrous rapidity has that sentiment faded! It is a certainty that these people have just aim to rebel, and perhaps even the rebellion itself is wholly justified, but I cannot with good conscience bring myself into support of such an undertaking anymore. As cruel the impositions of a King may be, and as shackled and constricted one is in these days, does one not bleed when breaking free of the chains? I have seen that to do away with the barbaric restrictions upon our people-hood will necessitate not a paltry cut upon our wrists, but rather a gash that will take more than the force of an entire nation to mend...

If I spoke in purely political terms I would surely condemn the rebels, but I am not a politician and do not aspire to be, hence I make my judgement by regarding the impressions they immediately make upon myself. And that is this: that they wish not to restore the Elder Ways, or bring forth a revolution that touches the deepest faculties of the human spirit, but rather that they are a bumbling mass of indifferent men, willing to committ violence and violate splendid innocnce with such ease.

I thoroughly despise speaking against my kinsmen, whom are brothers to me, and these headlands-folk have such a nobility of song and kindness of disposition that may be able to regenerate the whole of Gilneas with the Elder Ways, but this does not but defile their hallowed traditions.

And yet, I feel that there is another part of myself that clamors in the violence, and the chance of revolution, however small that may be. The wildness of the crowd, the beating heart of the mass, the frenzy of the riot - I wish both to embrace it in the name of dynamism and repudiate it in the name of civility simultaneously. My thoughts are muddled and unclear - why I ought refrain from the musings of society and bask only in the sweet hymn of the Elder Ways, the Drur-la, to which my life may be dedicated to alone,

Ferenold Stormshend.

This entry was written shortly after Ferenold returned from the town of Llareny to Farlund's cottage. It was three weeks after this was written that Farlund passed away.

Re-uniting of the Stormshend family.[]

The re-uniting of the Stormshend family refers to the period from 1042-1045 in the Gilnean calendar in which the Stormshend family lived to-gether in their country manse, located upon the tip of the Headlands.

The day that Farlund died, Ferenold resolved to continue his work and to take residence within Farlund's cottage. However, unlike Farlund, Ferenold believed that it was necessary not only to further develop and preserve his own knowledge of the Elder Ways, but also to teach other peoples of it. A self-styled prophet, he attempted at giving several speeches and teaching the Elder Ways within the town of Llareny, but amidst the revolutionary fervor of the Northgate Rebellion he was almost entirely ignored.

His failure to find any apprentice's of his own, as well as his remorse following the death of Farlund led him back to his parents once again. In spite of his attempts at repressing their memory and 'freeing himself' of his roots, he was led back to them. He first headed to the city, where he resided on what little coin he had for a period of six days before discovering that they lived in their manse at the Headlands. Several journal entries of Ferenold attest to the man's attitude at the time. The following one was written directly after Ferenold arrived in the city:

"It has been a folly, to hack and slah at the earth from whence I grew: Farlund warned me of it, but as some manner of a fool I ignored his preachings that were most direct and most personal, focusing solely upon the more spiritual aspects of the Elder Ways. Hence I have become something of a contrived and artificial man, the decadence I despised quickly having overwhelmed myself. What a pitiful creature I am!

That young wilderness man, freed from intellectual pretension, has fully vanished: he was only present amongst my younger years with Farlund, running carelessly - and meeting with the lady of the lake. I must be necessity confront that world: but I must no longer be some contrived moralizer, for Farlund was never a contrived man, never spoke his words as some manner of a manipulator.

I have at least been blessed with the freedom from this city, where all of its inhabitants bear but mechanical strides and speak but hollow words."

The next one was written after Ferenold left the city:

"I have discovered their place of residence from a man whom was once an employee of Thomas...the business has been shut down, the workplaces all gone. I must pray that they do not live in poverty, and that they moved into this headlands house to experience the greater joy of the country-side, rather than because they now live in squalor. Perhaps this shall at last bring a degree of solace into my life, but I fear with all the grand tumult rolling over Gilneas, little peace shall come to me."

It took Ferenold a single day from there to journey to the Manse, and he was graciously recieved by a servant, whom led him to Thomas and Emilia. Surprised, angered, shocked, but above all in a state of newfound exaltation, the parents welcomed Ferenold home with unhindered ceremony. It was a most joyous day, and Ferenold found that his father, once the cruel disciplinarian, had calmed considerably amidst the Headlands.

It was a most dramatic change for Ferenold, of course. Once living in the relative poverty of Farlund's hut, he at once was ascended to the position of wealth and prestige once again. Thomas had some manner of urban intrigue with the Elder Ways, though hesitant to take them on himself. Emilia displayed quiet approval of thtem, and idid a small amount of rudimentary work trying to form a union between the two faiths.

Ferenold interacted with his father a great deal. Previously, the two of them were relatively separate from each other. As a child, Ferenold almost solely saw his mother, and the times in which he did see Thomas the discussion was always curt and closed. But now their relationship underwent a new blossoming. The estate was a most spacious place, and the two of them often went off to fish and to take journeys by Earl'forth with the dark-wood boat that Thomas owned.

Thomas grew to be a man that was enamored with life, consistently bubbling with humour and mirth in contrast to the conflicted solemnity of Ferenold. The two developed a repor together though, and it seemed as if they were re-enacting what ought to have happened in the years of child-hood. They engaged often in philosophical discussion, but more common were their musings upon the idiosyncrasies of the headlands folk and the local wild-life of the headlands.

It was also during this time that Ferenold's thought truly came to bloom - in the confines of Farlund's cabins and the small villages of the headlands he had little access to those grand texts which touch the common spirit of men. In the headlands manse Thomas Stormshend had accumulated a library of various texts which Ferenold studied with fascination. Although he was not drawn to the more rigid analytical philosophy, he read from an early age the romantic-inclined philosophy of idealism, and most other forms of continental philosophy.

He gradually learned to justify his foray into the intellectual world and his growing participation in society through the 'organic' philosophies of several Gilnean philosophers: which have the belief that society out to arise 'naturally', from the bosom of the earth. He briefly was intrigued by the proto-marxist philosophy of several acclaimed academics, but eventually took the belief that they were merely a 'turning upon the head' of borgiousie capitalism: a negative reverse of it.

Above all though, his spirituality and faith in the Elder Ways, the world as an animated, living creature that shaped his patterns of thought in these years. Often escaping into the woods to perform his own rites, when he returned he sought only to synthesize all that time-honoured philosophy with the Elder Ways.

Ferenold also grew fond of artistic and musical productions during this time. Though never fashioning himself a member of 'high civilization', he nonetheless attended numerous musical productions with his father during these years. He writes of art and music in his journal:

"The artistic and musical are manifestations of the soul of man: that is, they respond to his most core urges and desires. The greatest pieces of arwork and music are synonymous with the very -idea- that animates a culture, and hence when heard by the members of that respective civilization, they enter into a state of dream-like reverie, essentially -losing- themselves within the composition. They are the Elder Ways of the urbane man, in many respects..."

His venture into philosophy was largely over-shadowed by his refound love in the written word, though. He wrote several short stories during this time period, and began to work on the manuscript that would later contribute to his most popular book, "A Mythos of Gilneas". Eventually, he tired of his writing and sought to teach the Elder Ways once again. He enrolled in several teaching classes at a small university, but ultimately his goal of teaching the Elder Ways was postponed by the Worgen Crisis.

The Worgen Crisis.[]

The Worgen Crisis refers to the period between 1042-1046 when the Worgen threat grew rapidly, eventually forcing the evacuation of Gilneas city, which eventually led to the widespread evacuation of all Gilneans from the country-side and into 'defended' areas. There was an unspoken rule in the Stormshend household not to speak of the Worgen, or the Worgen crisis, largely because the thought of abandoning the current life at the manse was too unbearable to hold.

Hence for the first three years of the Worgen Crisis, there remained relative silence in the Stormshend household over what ought to be done and where they ought to flee, if it came to that. Ferenold's knowledge of the Worgen was confined solely to the various murmurings which he manaded to pick up from the nearby villagers, and he willingly chose to ignore them. But of course, the Worgen were a very real and physical threat whom could not be perpetually ignored.

When the village nearby was attacked in the year 1046, the question forced itself upon the family. Seeing no escape root from the maurading Worgen, Thomas proposed locking the house in with a supply of foood. The proposition was met by a great amount of protesting by both Ferenold and Emilia. Ferenold's journal from the day attests to the stride that soon overtook the household:

"Thomas to-day proposed locking us within our household until the Worgen threat subsided...while this certainly may seem advantageous to our well-being if a man's sole guiding principle was impulse, I find that after careful contemplation it is the worst of all possible decisions. In all situations, this plan shall bring us to some degree of ruin, whether moral, spiritual, or physical...

Assuming that this plan succeeds, and from the vast multitude of outcomes in this situation the one which we strive for and dream for is pre-destined, even then we shall be doomed to imfamy. We, locked in some manner of a fort as our kinsmen band together in the struggle for the humanity and life of a nation, lighting our hands by the fire in bitter cowardice...we shall surely be deemed cravens by any man with sense. We shall be brandished with the marks of traitors, shamed by men emerging from the ecstacy of victory - and what is more, our very conscience will have departed us!

But if the very opposite occurs, and our country is indeed over-run by the feral wolf-beasts, some heaven-sent plague upon land, then we shall surely be the ones most likely to perish. While some shall escape up to Silverpine and to Lordaeron (If they have not already been ravaged by the Worgen Blight), we will be utterly surrounded in a land with no friends by the time we run out of food and must leave the manse in search of it.

I hear that the Northgates have at last been let free from prison - they, the men considered the worst of criminals by the Greymane Government, are openly cooperating with them. All of Gilneas is indeed being brought under a single bough by these beasts, except for my father, always stubborn. I pray dearly that my mother's somber pleadings will grant him a change of heart."

Later that same day, Emilia gave in to Thomas' demands and ceased arguing with him. Over the course of the next seven days a large amount of various supplies were bought by the Stormshend's from the villages about them - hoping to quite literally make their house some manner of a fortress that they could stay inside until the thread of the Worgen permenantly subsided. They knew not how much time it would be until Gilneas found peace - but they were determined to have their own until the entire nation did.

For four months the Stormshend's stayed within their household, through the evacuation of most Gilneans. They rarely, if ever stepped out of the household. The gardens, once a past-time of Emilia, withered as she was forced to stay inside the house, and Ferenold was no longer able to wander the forests and perform his own rites. If there was some manner of a 'tyranny' imposed upon the house by the father, it was certainly not recognizable under the familial backdrop of the manse.

With the family closed from the out-doors and their respective pursuits, they grew closer to one another than ever before. Their sole companions were another, and their sole shelter was with another: they had no knowledge of whether there was a surviving Gilnean resistance. Ferenold started exhausting the energy he once dedicated to the Elder Ways themselves and their religious practice into writing texts upon his own experiences with the Elder Ways.

Much time was spent amongst the library of the household by Ferenold and Thomas alike, pouring over old texts where there was naught else to do. In the evening, the family gathered by the fire-place each night and spoke amongst themselves. For the most part, the family lived in far better material conditions than other Gilneans, sleeping in beds with heated fires nearby, and eating food thoroughly cooked. But their emotional condition was poor- being split from all other Gilneans, fundamentally isolated from them, and having absolutely no knowledge of the fate that had befallen the country.

The cries of the Worgen were steadily intensifying, as well. It was clear by the four month of their stay within the household that a large band of them had taken up residence within the Headlands. They were heard howling and shrieking, creeping and leaping amongst the forests about the mansion. The couple was beginning to fear a break-in by the feral beasts more and more, but luck visited them.

The Evacuation.[]

On November 16th, year 1046 (Gilnean Calendar) the Stormshend's recieved their first village in months - or rather, several visitors. There were fourty-seven peoples in total, fifteen of them a member of a self-styled militia, and another twenty of them bearing arms. The core of them, the fifteen militiamen, were all from Gilneas City. They were upon a self-appointed mission to round up any remaining survivors from the headlands and bring them down to where the remaining Gilneans were massed: Duskhaven.

The leader of them was a burlesque man by the name of Theodore Comte, once a member of the King's royal guard but now bearing all but scraps of his former regal attire. The rest of them were considerably less distinguished. Several of them were former Northgate rebels that resided within the city, others criminals, and a few of them were recruits formerly enlisted in the Gilnean army.

The refugees primarily shared the same fate as the Stormshend's: they had decided to board themselves in, instead of traveling with the other refugees. Others were less fortunate. Several men and women were injured to a point where they could no longer move, and only the field-medic that accompanied the soldiers could relieve their wound. Regardless, they were all to-gether, and were a considerably scrappy bunch.

The Stormshend's were one of the last groups that they visited. The lights were dim in the manse, so dim that the manse seemed to emit no light from the outside. The militia gandered at first that the place was completely abandoned, but they visited it having some hope that there would be food left behind in the manse which they could pilfer. It was with great surprise that they found the well-kept and well-groomed family that still inhabited the place - and it was an equal surprise for the Stormshends.

They relented to allowing the group to inhabit the household for a single night - it is not as if they had much choice, anyhow. They were eager for some degree of company after the months of isolation, and there was something of a ball that took place that night. Ferenold would later comment upon the "Aged jolly that can be expressed by kinsmen, e'en thro tragedy's most embittering core."

Thomas had long ago conceded that the family may have been better off departing from the house months ago, and thus they made the arrangements to leave the manse and set off with the group toward the town of Duskhaven. They brought only their most dear possessions - Ferenold his stave and a small set of books, Emilia her rosary beads and most prized rings, and Thomas several quaint oddities that were formerly possessions of his father.

The group traveled in the night-time, as a single watchman could not rouse the group quickly enough to defend against an attack from the wolf-beasts, whom only attacked at night. They predicted that the journey to Duskhaven would take roughly a week upon the best of conditions. They fortunately possessed Ferenold, whom knew well the lay of the Gilnean land from all his wandering across it.

On the first night they managed to reach the broken down town-ship of Keel Harbour, almost completely deserted of all its inhabitants.

WIP

Battle of Stormglen.[]

WIP.

Wilderness Months.[]

Darnassian denialism.[]

WIP

The Re-awakening.[]

WIP.

Appearance[]

Standing at the height of five feet and ten inches, Ferenold is a well-toned, confident young man. His cheekbones are set high and pristine, face possessing a kindly and genial quality to it, filled with the mirth that a country-lad was wont to embody. The youth's eyes are deep set and of a stark blue, a quiet sort of intensity carried within them as they snapped about in short bursts of curiosity, while his brows overshadowed the arrangement, jutting out of his forehead in clear contrast to his in-laid eyes.

Ferenold's entire countenance looks to be storm-wrought, having a delicate balance between dignity and savagery, between civility and barbarity as a grecian statue of a germanic tribesman. To the man who observed Sir Stormshend scrutiny, his figure might even impart some sense of timeworn, antique nobility.

He is indeed one given to aristocratic posturings, carrying himself with a noble's eloquent gait despite the quick, over-accentuated movements of his mien. The man strode in the lordly march of ancient blood with not the dull mechanicity of an aged man, but all alit and aflame with the passion inherent in a Gilnean tempest. Whether he ambled forth in such a manner by mere arrogance or brashness was unknown, but it was made all the more striking because the disparity his gait had with his groomings.

What elegance that his face and gait might possess is misshapen at once by the dirt and grime strewn across his now-boyish visage. This combination lended itself to some manner of handsome ruggedness, as if in some futile attempt to ascend to the ideal of country Masculunity, yet never did the man epitomize it fully: for the strands of hair that fell idly upon his chest and his patrician-like stride had long ago prevented such archetypes from becoming manifest in the man.

Adding to the peculiar dichotomy present within the man is his right ear, thoroughly mangled and disfigured. While most scars burn bright upon a young lad as a seared symbol of manhood, the ugly sight on Ferenold's ear could never be championed as such a prize. It did little but detract from the man's appearance, being far too grotesque and unseemly a gash for any maiden to find becoming.

As for his body itself, he is not overly muscled, but his musculature nonetheless bore moreso the marks of labour than those of battle. The man's hands were calloused, his arms possessing definition, but not near the detail that a soldier's thick arms held. The only truly unique aspect of his figure aside from his countenance is his broad breast, which briskly thinned into a torso far leaner.

Provincial and rustic, Ferenold 's voice is enunciated with an accent characteristic of the peasantry of the Headlands: Southern-Irish, with a faint iota of a Scottish vernacular. His actual tone is far too wild and tempestuous to be ever considered that of a noble, tone lilting and wandering about like that of a bard in song. In a civilized function, his voice would most befit an opera singer rather than a politician - and when the man sought to speak with the precision of a man of rhetoric, his words sounded contrived and artificial, isolated from their source.

The man is found adorned in a great variety of clothing, but they have a single unifying factor: they are all manufactured in a Gilnean or Arathian fashion, and the great majority of them are anachronistic. Rarely is he seen in avant-garde fashions, and cosmopolitan fashions such as the top hat are seldom seen upon the man; when the are, they are ill-fitted to Ferenold.

Seldom if ever is the man seen in his cursed form - and there are utterly no signs that he is afflicted. There is no feral scent to be found upon the man, no stray 'dog-hairs' resting upon his person - not even the faintest iota of a hint that may suggest he is cursed.

Recently he has been seen with a leather scabbard at his hip, adorned with mythological scenes of Gilneas' past. Only barely visible is the hilt of a two-foot seax which protrudes out of the front of the scabbard, inlaid with both niello and gold.

References[]

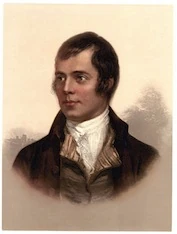

(Image:Ferenold.jpg, Alexander Nasmyth, 1787 )